Josephine Baker was an dancer, singer, and actress, who could fly a plane and ride a racehorse, plus she fought against racial prejudice in her native US, adopted 12 children, and was a decorated war hero in France- incredible!

In this series of articles, I’ll share mini biographies of some of my personal heroes. In true unpopcultures style, these people are or have been influential in their niche or specific time, but perhaps are not at the forefront of current popular imagination. We start here with the enigmatic Josephine Baker (1906- 1975), who was said to be the most photographed woman in the world and highest paid performer in Europe back in 1927!

I initially became aware of her as a dancer and the famous image of her performing Charleston routines while wearing a skirt made from bananas. As I began digging deeper, what emerged was her fascinating and varied life: she had been married twice by the age of 15, had a pet cheetah named Chiquita, was involved in the French Resistance during the Second World War, and she was friends with Princess Grace of Monaco, to mention just a few anecdotes.

What inspired me about her story, beyond her talent as a performer, is her bravery- she stood up for what she believed in and overcame many obstacles in her life. She was a humanist who didn’t see race, nationality, or sexuality as a differentiator, and a supremely adventurous person, keen to explore new experiences. Read on for more insight into this fabulous lady, starting with her performing career, her work to promote racial equality, and her intriguing personal life.

Dancing and performing

“… I improvised, crazed by the music… Even my teeth and eyes burned with fever. Each time I leaped I seemed to touch the sky and when I regained earth it seemed to be mine alone.”

Josephine Baker

Josephine’s performance style, that she describes here so beautifully, became iconic, but it would take time, struggle, and transatlantic move before this fully developed.

Born into a poor family of performers in St Louis, Missouri in 1906, Josephine began dancing at a very early age, both on stage and on the streets to earn money. Alongside this, she worked as a maid and babysitter for white families from age 8. She was treated poorly by her employers and ran away in 1919 at age 13. Later that year while working in the Old Chauffeur’s Club, she was “spotted” and picked up by a theatre group, The Jones Family Band, and began to tour the US.

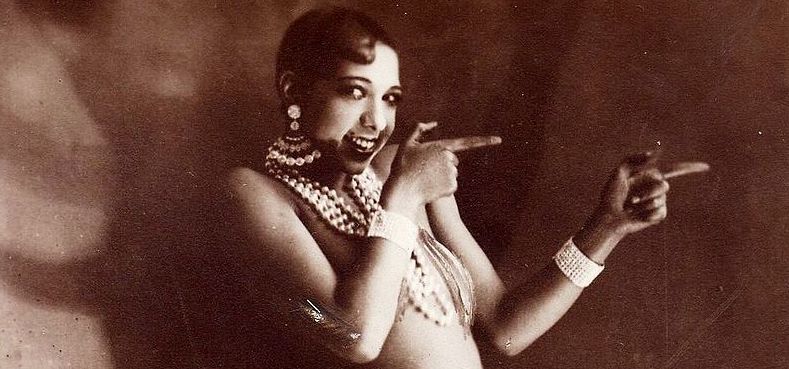

In 1921 she moved to New York City, attracted by the vibrant atmosphere of the Harlem Renaissance, a time when African American art, literature and culture flowered in response to an influx of migrants from southern states. She performed in several Broadways shows, including the seminal (all African American) Vaudeville review show, Shuffle Along. Playing the funny girl at the end of the chorus line, she would pull faces and purposefully mess up the choreography, only to come back on for the encore, performing better than the other dancers. Audiences loved her stage presence and critics began to notice her talent, singling her out in their reviews, and she became billed as “the highest paid chorus-girl in vaudeville”.

Josephine on stage (Walery 1926, source: Wikimedia Commons)

Josephine was ambitious, but it became clear that Jim Crow segregation laws and climate of racism would hold her back and mean she could only access certain roles in the US. While art and culture were flourishing within African American communities, black performers appearing before white audiences would often either “black up” or lighten their skin, so the audience would assume they were white or non-threatening. Outside of the theatre, African Americans could not enter certain restaurants or hotels, and were very much treated as the inferior “other” in white society.

It would be in France not the US, where Josephine thrived and rose to true superstardom. In 1925 aged 19, she moved to Paris to star in the review show, Revue Nègre. Here she encountered a very different attitude towards her race: there was a popular and fashionable interest in African art and culture due a fascination with the French colonies in West Africa. Her first performance created a sensation as she appeared almost completely nude, and reviewers likened her to a beautiful African sculpture brought to life! She even became a muse of influential artists and writers including Picasso, Ernest Hemingway, and Jean Cocteau.

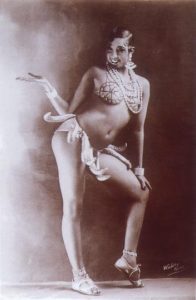

Her star was rising and she was quickly snapped up to star in the La Folie du Jour at the Follies-Bergère Theater, one of the top shows in the city. It is here that she developed and popularised her unique style and was appreciated as a solo artist, debuting her iconic Danse Sauvage performance in 1927, wearing her infamous skirt made of 16 bananas.

Josephine in her “Girdle of Bananas” (Walery 1926, source: Wikimedia Commons)

As a dancer myself, I’m particularly interested in Josephine’s movement style. She made use of classic jazz and Charleston steps that were popular in the 1920s, such as snake hips, knee knocks, mess around, shimmy, tack Annie, and the shorty George. She performed these with a grounded posture and low centre of gravity, inspired by African movement and breaking away from the upright posture and tight, disciplined form of “European” classical ballet.

She was also sensual, incorporating hip rotations and sways and a free and fluid movement with her lower body. One reviewer described her moving with a rubber-like quality and as if she had no bones in her legs! Contrasting with this sensuality, she would knowingly “break” a sexy routine with comedic and silly elements: dance theorist Anthea Kraut, notes her “distinctive knack for crossing her eyes”!

Many images show her epitomising the 1920s Charleston and jazz poses, but it’s the video clips that really bring to life her energy that was so iconic. Cultural historian and choreographer, Brenda Dixon-Gottschild, describes her as moving with “heroic exhibitionism”, possibly the most wonderful description of a dancer’s style I’ve heard! Ultimately, she combined the sensual, wild, and comedic in one electrifying package.

Here is Josephine performing in a silent film, La Revue Des Revues in 1927, directed by Joe Francis (this is safe for work i.e. no nudity):

As her performing career progressed, she focussed on singing and acting. She appeared in silent films such as Siren of the Tropics (1927), Zouzou (1934) and Princesse Tam Tam (1935). She continued to work with a vocal coach through the 1930s, and starred in Jacques Offenbach’s opera La Créole in 1934. Quite an incredible move from dancing on the streets of St Louis to the refined theatres of the Champs-Élysées!

Race and fighting discrimination

“Surely the day will come when colour means nothing more than the skin tone, when religion is seen uniquely as a way to speak one’s soul; when birth places have the weight of a throw of the dice and all men are born free, when understanding breeds love and brotherhood.” Josephine Baker

As we can already see, race is an important theme in Josephine’s story. The topic of the representation of race in her performances has been much debated. Even while celebrated in France, she was largely limited to portraying the “primitive savage” on stage, especially in her 1920s dance performances. Some theorists including Anthea Kraut argue though, that a closer reading reveals that her injection of the comic, transforms the performance into parody and works to subvert the stereotypical image she portrays. She is perhaps then, far from “powerless”.

This power is reproduced beyond the stage, where she would become a staunch supporter of the civil rights movement in the US. Inspired by witnessing terrible violence in the St Louis race riots of July 1917, she would fight hard to overcome many barriers along the way.

Josephine made a return to her native US in 1936. She was invited to become the first African American to perform in the Ziegfeld Follies review show in New York, alongside some of the biggest white stars of the time, Bob Hope and Fanny Brice. Despite being a superstar in Europe, Josephine received poor reviews and even was called a “Negro wench” in Time magazine. She was also shocked by the racial segregation and poor treatment of African Americans, and returned to France, where she took her citizenship in 1937.

Not one to give up, she visited the US again in 1951. She was invited to perform a sold-out run at a club in Miami, but refused to do so unless the audience were desegregated- an historic battle that she won. She embarked on a national tour, only agreeing to perform to mixed audiences, and was greeted in Harlem by a street parade of 100,000 people!

This success however, was short-lived. When dining in the Stork Club in New York, a popular spot for movie stars and singers, her party were given poor service due to racial discrimination. She made a very public complaint to the manager and stormed out, vowing never to return. In the club that night was pro-segregation columnist Walter Winchell, whom she criticised for failing to assist her. Unfortunately, he took against Josephine and published articles accusing her of communism. In the political climate of the emerging Cold War, this was a damning accusation, and led to her visa being revoked and she had to cancel her remaining shows and return to France.

By the 1960s, attitudes in the US were in the process of shifting. Josephine lent support to activism and participated in the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where Martin Luther King delivered his “I have a Dream” speech. She was one of the few women asked to formally speak. She talked about the stark contrasts between her treatment as a black woman in the US and elsewhere:

“You know, friends, that I do not lie to you when I tell you I have walked into the palaces of kings and queens and into the houses of presidents. And much more. But I could not walk into a hotel in America and get a cup of coffee, and that made me mad.”

Her efforts were later recognised by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), who named May 20th Josephine Baker Day in honor of her work. In 1973 Josephine agreed to perform at New York’s Carnegie Hall and received a standing ovation even before she had started to perform, showing just how far attitudes eventually progressed in her lifetime.

Life off the stage

“Since I personified the savage on the stage, I tried to be as civilized as possible in daily life.”

Josephine Baker

While her daily life might have been “civilized”, it certainly wasn’t boring! She was adventurous with a desire to learn new things, including how to ride a racehorse and fly a light aircraft. Josephine extended her equalitarian and humanist attitudes about race to her sexuality, having relationships with both men and women. With a clever eye for marketing, she also had a pet cheetah called Chiquita while living in Paris in the 1920s. She would walk it down the Champs-Élysées, leading one journalist to question: “which end of the leash holds the wild animal?!”

Josephine in military uniform (Harcourt 1948, source: Wikimedia Commons)

More seriously though, as we can see from her civil rights activism, Josephine was not afraid to get involved and contribute to change. At the outbreak of the Second World War, she began working for the French Resistance, using her position as a famous performer to travel throughout Europe gathering intelligence. She attended parties at embassies and used her charm and star power to gather valuable information, smuggling notes on troop movements written in invisible ink inside her sheet music, and pinned to her underwear. She achieved the rank of Lieutenant in the Free French Air Force, and in 1946 was awarded the Croix de Guerre, the Medal of the Resistance, and made a member of The Legion of Honour, the highest military award in France.

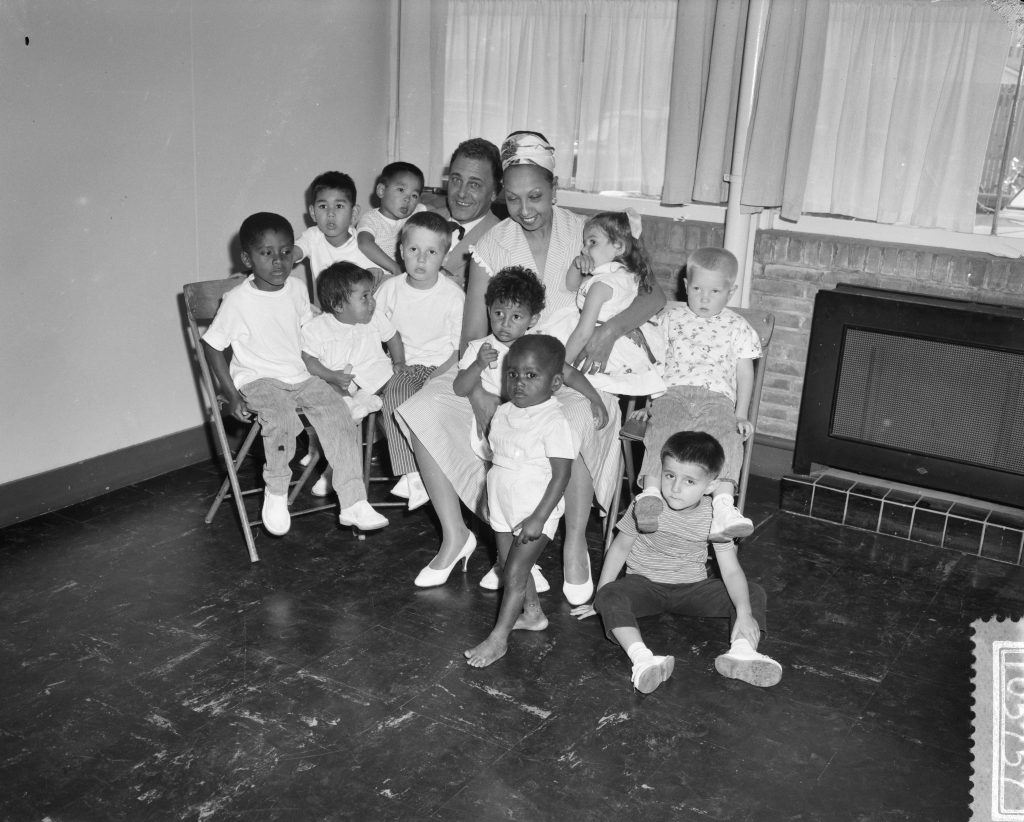

Her family life was equally remarkable: having been married twice by age 15, she married again after the war in 1947 to orchestra leader, Jo Bouillon. Unable to have their own children, Jo and Josephine adopted a total of 12 children of different races and ethnicities in the early 1950s. Affectionately referred to as “The Rainbow Tribe”, they all lived together in her Chateau Les Milandes in the south of France. She wished to set an example that people of all races have no intrinsic differences and are all one family- civilized, indeed!

Josephine and Jo with 10 of The Rainbow Tribe (Herbert Behrens 1959, source: Wikimedia Commons)

Josephine at the Chateau Les Milandes (Jack de Nijs 1961, source: Wikimedia Commons)

Later life

“I love performing. I shall perform until the day I die.”

Josephine Baker

Josephine performing in Amsterdam in 1960 (Harry Pot 1960, source; Wikimedia Commons)

This is one of my favourite quotes from Josephine and one that would turn out to be prophetic. Despite having been one of the most famous people in the world, in her later life, money began to fall short. Under strain from supporting 12 children and running the Chateau, Josephine was bankrupt by 1969, and sadly lost her estate. Friends would come to her aid, including Princess Grace of Monaco, who took them in and gifted her a property in Monaco.

Josephine returned to the stage, both in Europe and the USA in the early 1970s. On April 8th 1975 she opened a series of performances at the Bambino Theatre celebrating the 50th anniversary of her Paris debut. At age 68, she performed a medley of 34 pieces from throughout her career, and received rave reviews. Just four days later on April 12th, she died in her sleep of a cerebral haemorrhage.

To mark her incredible legacy, she was honoured with a 21-gun salute at her funeral, the only American-born woman to have receive full French military honours, and has a street named in after her in Paris (Place Joséphine Baker in the Montparnasse Quarter).

As we approach the 20s again, I’m going to try to be a bit more “Josephine”- courageous, adventurous, open in my attitudes, and full of love for humanity as one. I’m also going to work on my Charleston and cross-eye skills, and dedicate my dance practice to this remarkable lady on May 20th!

Thanks for reading! Hit Follow to receive brief notes letting you know that I’ve posted a new article, and in the meantime, check out the Instagram and YouTube channels for more (Un)Popular content!

Resources:

- Kraut, Anthea “Between Primitivism and Diaspora: The Dance Performances of Josephine Baker, Zora Neale Hurston, and Katherine Dunham,” Theatre Journal 55.3 (October 2003): 433-450.

- A biography written by one of her son’s: Baker, Jean-Claude (1993). Josephine: The Hungry Heart. New York: Random House.

- Official website and biography here.

- Interview with Josephine from 1975 here.

- Joséphine Baker: The 1st Black Superstar, Forget About It Film & TV, for BBC Wales. 2006. Narrated by Josette Simon. Directed by Suzanne Phillips.

- Chasing a Rainbow: The Life of Joséphine Baker,1986. Channel Four Films & Csaky Ltd.

Great post Zoe.

Well told tale of an exceptionAl woman and a real hero.

Thank you for this. Josephine is so inspirational