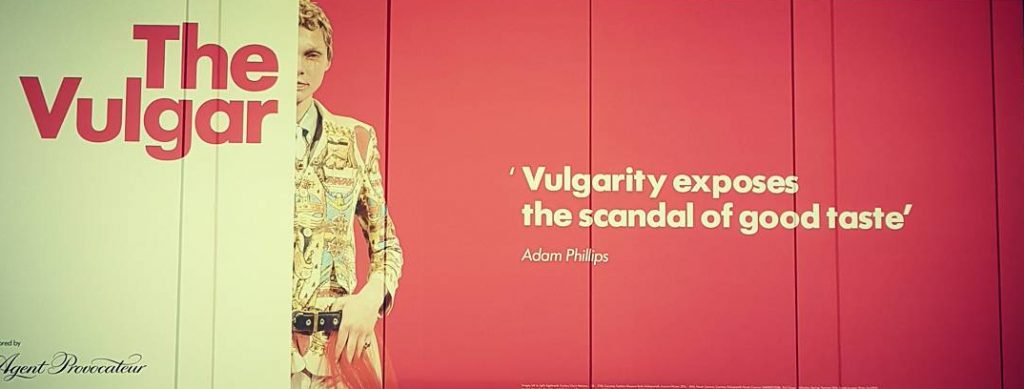

In this series, I share my experiences of visiting exhibitions that have inspired or surprised me. I start with “The Vulgar: Fashion Redefined” at The Barbican (13 Oct 16 – 5 Feb 17), and a Q&A evening with the curators, in which the the role of vulgarity within fashion and society is thoroughly challenged…

How would you define “vulgar” fashion? I hadn’t given it much thought, and simply expected outfits composed of a bricolage of too many colours and influences clashing together, exaggerated shapes and unconventional fabrics, and a few overtly sexual or revealing items. While the exhibition did feature pieces such as Vivienne Westwood’s “Tits” T-shirt, and a flamboyant couture gown from John Galliano for Dior, the experience was much more thought-provoking than simply enjoying weird and wonderful (anti)fashion eye-candy.

Curated by Judith Clark, Professor of Fashion and Museology at London College of Fashion, and Psychoanalyst, Adam Phillips, the exhibition explored over 20 categories of meaning through exhibits from 500 years of fashion history. In this post, I’ll explore how it challenged visitors to think more deeply about the uncomfortable histories and definitions of vulgarity, explored how the fashion industry has played with the concept, and revealed the surprising violence of this term.

Origins of the vulgar

The term vulgar comes from the Latin, “vulgus” meaning “common people”, and was originally used to refer to anything vernacular, familiar or ordinary. It quickly took on class connotations and was used as a tool to define socio-economic divides; an insult used by elites to “other” those considered lower in economic and social status.

There was a profound but subtle shift in this definition from the 18th Century. Social changes as a consequence of the Industrial Revolution, meant that wealth was not only inherited, but could now be earned. As a result, vulgarity could no longer be correlated simply with wealth, but had to become more nuanced- it became about knowledge, a knowledge only accessible to those of “good breeding”.

For example, quoted in the exhibition is a section of an etiquette guide for ladies from the 1880s. It notes that “well-bred” people were not seen in the latest or most extravagant fashions, as these had become mass produced and so considered too readily available. Equally, wearing jewels, gold, and lace was no longer a guarantee of being “well-dressed”- this could be considered “too much“. The middle classes of the 18th Century, may have worn expensive, extravagant clothing (on display were dresses with enormous panniers, covered in intricate lace and decadent jewels for example), but they were viewed as “nouveau riche” pretenders who did not truly achieve good taste. Their clothing was simply a copy or imitation, and a poor copy at that, of what was perceived to be good taste.

“The scandal of good taste”

The exhibition demonstrated how the controversial implications of the “poor copy” have continued over time. A display of magazine clippings opened discussion of how immigrants are often considered vulgar, as they wish to integrate and replicate the status quo, but portrayed as never quite getting there. Speaking from personal experience, in the Q&A talk, Adam Phillips revealed how the anxiety of being considered vulgar featured strongly in his upbringing in a middle-class Jewish family in Cardiff. Surrounded by anti-Semitism, Phillips recalls sensing his mother’s fight to “fit in”, and her anxiety at wishing to avoid being considered vulgar by Gentile friends, who described other Jewish families as such.

In this sense, the vulgar works to “reveal the scandal of good taste” (Phillips)- the scandal of impossibly promoting something as a universal truth, but only achievable by the few. This act of defining standards of good taste versus vulgarity is a violent act with no possibility of a grey area- you’re either vulgar or not, in or out.

When thinking through these definitions, the exhibition uncovered uncomfortable histories and associations with prejudice that I had not previously considered. I had simply assumed that vulgar was one of those throw-away terms, that you “just know” what it means, and did not seriously consider the power implications in its use. As Phillips concludes:

“by being too insistently visible we forget that the vulgar has histories and purposes”

![By Mabalu (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://unpopcultures.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Trompe_loeil_printed_viscose_jersey_dresses_by_Maison_Martin_Margiela_1996_and_2012-169x300.jpg)

Left: Maison Martin Margiela, S/S 1996. Viscose jersey printed with trompe l’oeil print of a sequinned evening gown. Right: Maison Martin Margiela for H&M, 2012. Viscose jersey printed with trompe l’oeil print of a sequinned evening gown. (Source: Wikipedia Commons)

Vulgarity and the fashion industry

The fashion objects on display were diverse- many could be described as “intellectual”, with several self-consciously pointing to the role of the fashion industry in playing with the boundaries of good taste.

One of my favourite pieces on display was Maison Martin Margiela for H&M Trompe L’oeil dress (2012). This dress constructed from a photograph of an elaborate sequined gown printed on a simple viscose t-shirt style maxi dress (right in image). This was a re-edition of a design from a 1996 collection (left in image), which was itself constructed from a photocopy of sequins. This object, as a copy of a copy of a copy, sold at a high street, “fast-fashion” retailer, points to the challenging nature of the copy in fashion industry, which is dependent on constantly producing something new for survival.

The vulgarity of exhibition

Going one step further down the rabbit hole, and the exhibition itself is designed as a comment on vulgarity. Displaying fashion in a museum setting can be considered vulgar- placing something popular, accessible, and commercial such as fashion within a context that usually holds exemplars of “high culture”.

It wasn’t until 1983 that a museum (the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York) ventured beyond displays of historical costume, to feature Yves Saint Laurent as the first living designer to have an exhibition dedicated to their work. In honour of this, on display were dresses from his classic Mondrian Collection (1965). Inspired by paintings, these pieces also reference debates about originality and value in the fashion industry.

Complicit architectures

A fascinating feature of the exhibition was how the architecture of the gallery was used as part of the mission to challenge assumptions – to veil and then reveal. For example, a mesh screen and lighting were used in one gallery to project shadows of conventionally glamorous silhouettes e.g a sleek maxi length evening gown, a classic men’s suit, and Edwardian tailoring. When turning the corner, these expectations were subverted, as the objects were revealed to be Mui Mui’s AW16/17 collection made entirely from denim. This bricolage of high-value cuts with traditional workwear fabric, historically associated with youth culture, points to how vulgarity has been used within fashion industry to challenge and disrupt.

Geographies of the vulgar?

The exhibition clearly showed the temporal elements of the vulgar and how the definitions had changed (or not) over time, but I wondered whether there was a spatial element also. Feeling brave, I asked a question of the curators at the Q&A session:

Is “vulgar” a global concept consistent across cultures, or is it limited to the “West” or the English speaking world?

Clarke noted that although the exhibition scope was focussed uniquely on the meaning of the term in the “English language” and from a “Western perspective”, the exhibition will next travel to Vienna, with an interesting modification: the name has been changed to “Vulgar?” with a question mark. This was because the term in translation was believed to be too “harsh” and off-putting in an Austrian cultural context.

At a more local scale, milliner Stephen Jones, touched on the potentially complex geographies of the term in his video interview featured in the exhibition. He noted how wearing the same object – a crocodile handbag – is considered “proper” in the countryside, but “vulgar” in the city.

Vulgar definitely appears to have a spatial or contextual element, and I wonder what, for example, an equivalent might be in Japan, a socialist country such as China, or even closer to home with Scandinavia’s “Law of Jante” concept, where no one considered above another? Does the term perform the same violence within these cultural contexts? It seems that there are further layers of complexity when this term travels.

The future of the vulgar?

Through examining 500 years of fashion history, the exhibition suggests that (in the Western, English speaking world at least) there is a consistent drive for elites to define and separate good taste from vulgar fashions to reinforce their position in society. However, what might the future hold?

The exhibition references the excessive displays of wealth seen in contemporary fashion practices of widespread Hip Hop cultures, and revealing outfits of beloved pop artists such as Lady Gaga- well bred people of the 1880s would not approve! What is the future of vulgarity when such excess is now the norm? Is there potential for this definition to be democratised, or will it remain in the hands of elites? Perhaps this could be challenged when there is no consensus, or when people refuse to play the game. Perhaps power may shift to a different group of “elites” entirely?

Finally, could the term “vulgar” be reclaimed and even seen as a positive attribute?

Certainly, if vulgar is seen as a lack of knowledge of good taste, might this have potential to open up a unique space for creativity and free thinking?

What are your definitions of the vulgar? Do you think it can or will be viewed as a positive attribute in future? Please leave a comment and follow for updates on future articles!

![By Yves Saint Laurent (photographed by Grey Geezer) (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://unpopcultures.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Mondrian-2017-04-22-2-scale-153x300.jpg)