Described as the “matriarch of black dance”, Katherine Dunham pioneered a dance pedagogy fusing classical ballet with African-rooted dance and rituals. She was a remarkable anthropologist, choreographer, and founder of the first self-supported African American dance company in the 1940s.

Ms Dunham revolutionised modern dance, pioneering a style combining classical ballet with movements rooted in the aesthetics, values, and body mechanics she experienced in her anthropological fieldwork across the African diaspora. Through this work, she paved the way for African American and other people of colour to play a role in dance as “high culture”, rather than limited to stereotypes in minstrel or variety shows that dominated in the 1920s and 1930s. She was also involved in political and social work, plus she influenced many other dancers, including a young Alvin Ailey, who’s dance company continues to tour the world today.

I knew surprisingly little about Katherine Dunham before this series digging into inspirational African American cutural influencers, despite having studied the closely related field of contemporary dance. I always particularly enjoy the elements of dance that “break the rules” of ballet- a flexed foot, a spinal release, a moment of grounding, a non-classical musical accompaniment. It was fascinating to learn that Ms Dunham was amongst the first to introduce such ideas in the 1930s and 1940s- I hope you’ll find it interesting too!

Academic and dance career

Katherine Dunham was born on June 22nd 1909 in Chicago. From being a young child performing in church, Dunham had wanted to follow a career as a singer, but she was academically talented and so encouraged to study to become a teacher like her older brother. In 1929, she started at the University of Chicago and was one of the first African American women to be awarded a degree from this institution.

It was at this time that she studied ballet and also became interested in the anthropology of dance from her own cultural roots. In 1936 she was awarded an anthropology scholarship and travelled to various Caribbean countries, including Jamaica and Haiti, to begin her work on the cultural anthropology of dance in the African diaspora (i.e. peoples of African heritage living outside of the African continent).

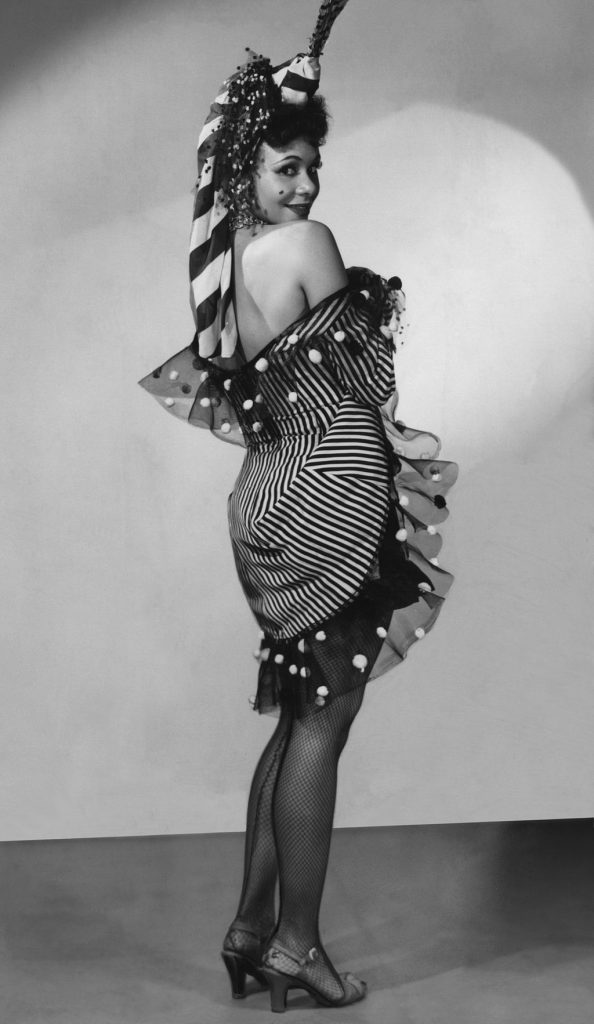

Katherine Dunham in 1940

She went on to conduct extensive research across several Caribbean, South, and Central American countries throughout her academic career, investigating the form of dance, and its role and meaning within society and sacred cultural rituals. Dunham published several books and articles, but she was far from solely an academic: she embedded herself within these cultures, built trust, and even became a practitioner of the rites of vodun (voodoo) while in Haiti.

Dunham was also a dancer herself and began to find the techniques she had learned through ballet insufficient to express the stories she wanted to tell about herself and about the cultures she had experienced through her research. This was something Dunham was enduringly passionate about- in an interview several decades later in 2005 at aged 96, Dunham was asked what the purpose of dance is for her:

“expressing your culture, expressing the meaning of your life, the meaning of the people that you came from, the meaning of your family and your roots…”

She developed her own dance pedagogy called the “Dunham Technique” (more on this to come), established a dance school in New York in 1944, and founded the first self-supported African American dance company, the Katherine Dunham Dance Company, to perform and share these ideas. Some of her most notable pieces include L’Ag’Ya (1938) based on a Martinique fighting style, Rites de Passage (1941) inspired by Caribbean fertility, puberty and death rituals, and Shango (1945) featuring voodoo ritual.

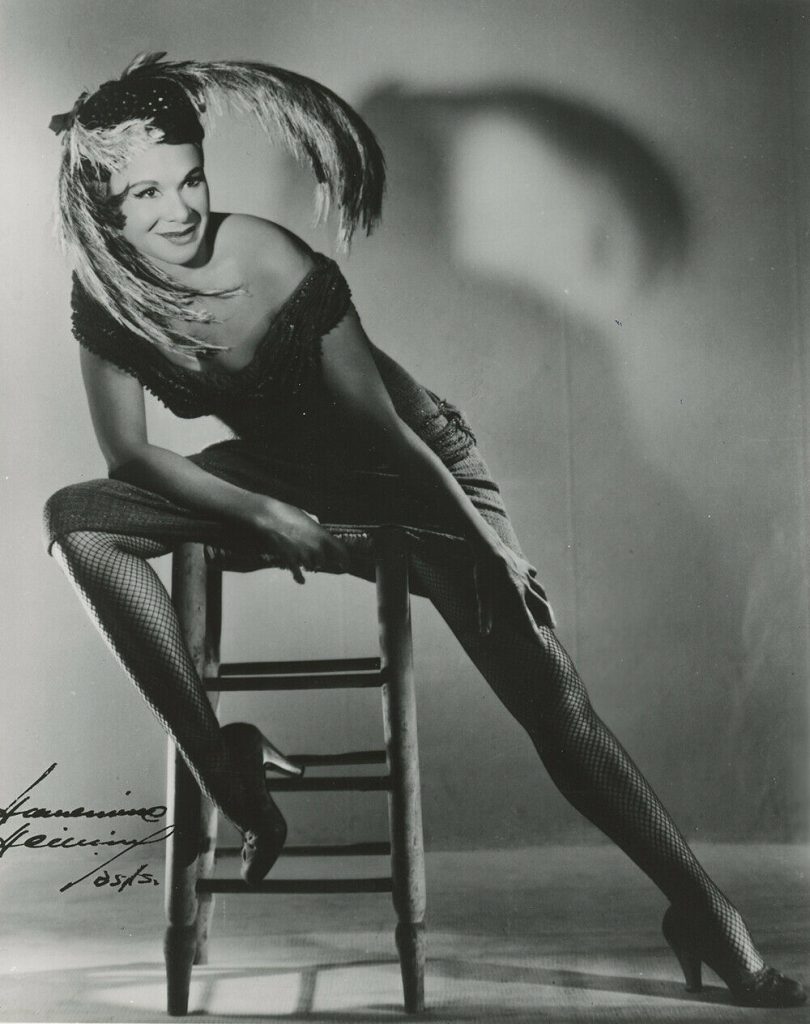

Katherine Dunham in “Tropical Revue”, 1943 (source: wikimedia commons)

Over her career, she would open further dance and cultural studies schools in Rome, Paris, and Stockholm and choreographed over 90 pieces for her company to perform in over 50 countries. Dunham and her dancers also choreographed and featured on Broadway stages in productions such as A Cabin in the Sky (1940) and in Hollywood movies like Stormy Weather (1943)- certainly many significant measures of success!

Take a look at a clip from Stormy Weather here:

Dunham Technique

There’s no way I’m going to write about a choreographer and a whole style of dance without properly nerding out on it, so here I’ll dive into the characteristics of Dunham Technique in a little more detail:

One of the foundational principles of Dunham Technique is envisaging the body as moving around a central spinal pole that is fixed but malleable. Characteristic movements include spinal undulations, movements driven by the pelvic girdle, the use of fall and recovery, and polycentric movements, whereby multiple body parts are isolated and move independently and simultaneously. These elements contrast with ballet and are considered to give the style a sense of comparative freedom.

Watching footage of Dunham describing her technique and working with a student, she explains how the arms are thought of as moving from the central spinal pole, with a sense of extension and elongation. The hands are relaxed, but also thought to have a pole through the centre of the palm, and so move with a sense of dynamic resistance from this centre point. Equally, the foot, sometimes pointed, sometimes flexed, can be thought to have a centre of focus, and always using the floor to generate a sense of grounded movement.

In Dunham Technique, it’s essential to tap into personal energy and “soul”…

Additional to these principles, Dunham Technique is not just about learning choreography but about incorporating and expressing something about a dancer’s soul. Dunham talks of a “circle of energy” emanating from the central spinal pole, whereby “life itself” is released. In Dunham Technique, it’s essential to tap into personal energy and “soul” in the dance. Part of this energy comes from the dancers culture and background, and for Ms Dunham, performance was one way in which she was communicating her research findings beyond the written word.

I first became aware of Dunham’s work when preparing to teach a series of Blues dance classes inspired by specific African American dancers (another in the series was jazz dancer, Josephine Baker, for example). Her piece Barrelhouse (1938) features a couple dancing together and includes many movements that we have variations of in Blues, unsurprising since both are rooted in African dance aesthetics and values. It was a challenge to attempt to adopt some principles from this style and explore some of the foundational techniques mentioned above, including ideas of a pelvic gyration (almost a shimmy with the hips), and emphasising this with arm placement.

A clip of Barrelhouse:

Racial politics and social work

Ms Dunham developed a dance style influenced by African movement and performed largely by African American dancers against a backdrop of racism and segregation in 1940s. Her career was political throughout. She recognised the tension of receiving standing ovations after performing in theatres ther company would not be allowed to enter as a member of the audience due to the segregation laws in the USA. She spoke openly about this on stage, a very risky move at the time, and refused to give an encore when performing in Louisville, Kentucky in 1944, and later refused to perform in segregated venues.

She also reacted against discrimination while working in Hollywood, and turned down a studio contract when a producer insisted on swapping out some members of her troupe for lighter-skinned dancers. She directly confronted and explored race issues in her pieces, debuting a piece called Southland (1950) in Santiago, Chile, which depicted a lynching of a black man in the American South. Her personal life was also controversial as she married white costume designer, John Pratt in 1949, and they adopted a child together. Mixed race marriages were not common at this time and she was met with questioning from both black and white communities.

Dunham was socially conscious and did a great deal of community work to help directly working-class African American people. She moved to St Louis in 1964, a time in which the city was experiencing industrial decline and rising poverty and unrest, particularly in working-class African American neighbourhoods. She worked as the artist in residence at Southern Illinois University and in 1967 she became director of the Performing Arts Training Center.

…she encouraged gang members to visit the centre and learn drumming techniques to help vent frustrations and connect to their cultural roots.

She established social programmes in the arts and provided counselling to encourage local young people against crime and provide an alternative outlet and space for support. Following riots after the assassination of Dr Martin Luther King Jnr for example, she encouraged gang members to visit the centre and learn drumming techniques to help vent frustrations and connect to their cultural roots. She was even arrested by police during her work in these disadvantaged communities: despite being booked to perform that night, she did not tell the police her true identity so she could experience what working-class African Americans would go through and could truly empathise with them.

This political and ethical consciousness was something always with Duham, and even at the age of 82 in 1992 she went on a 47-day hunger strike to protest the US government’s policy for refusing to accept and repatriating Haitian immigrants. She was awarded the highest medal of honour by the Haitian President.

Legacy and influence

Joyce Aschenbrenner (2002), credits Ms Dunham as the “matriarch and queen mother of black dance”…

Kantherine Dunham passed away of natural causes on May 21, 2006, one month before her 97th birthday. Her legacy was far-reaching, both in dance and her cultural and social work. In her biography, Joyce Aschenbrenner (2002), credits Ms Dunham as the “matriarch and queen mother of black dance”, and describes her work as: “fundamentally changing American dance”. This contribution was recognised by receiving the highest awards for the arts in the US, the Kennedy Centre Honors in 1983 and the National Medal of Arts in 1989, and further awards from France, Brazil, and Haiti.

Katherine Dunham photographed in 1954 (source: Wikimedia commons)

Her anthropological contribution lives on through the museum she founded in St Louis with over 250 pieces from over 50 countries in the Caribbean, South and Central America. Her dance schools also had notable influence, including on legendary contemporary choreographer and dancer, Alvin Ailey. He states in his autobiography, Revelations (1995) that watching a performance of Dunham’s dance troupe when he was 15 years old inspired him to start dancing:

Seeing Miss Dunham and her company was a transcendent experience for me… I couldn’t believe there were black people on a legitimate stage in downtown Los Angeles.

His company, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, performed a tribute to Katherine Dunham at Carnegie Hall in 1987, and his company continue to tour the world today.

Sources and further information:

- Katehrine Dunham’s autobiography of her childhood: A Touch of Innocence

- Some of Katherine Dunham’s academic anthropological work in her: Island Possessed.

- Biography by Joyce Aschenbrenner, Katherine Dunham: Dancing a Life (2002)

- Library of Congress has many videos from performances and interviews, plus articles and a helpful timeline of her career.

- The Katherine Dunham Personal Foundation

I have loved researching Katherine Dunham’s contribution to dance, anthropology, and social justice: to discover someone who has excelled in so many fields is truly inspiring! I am going to hunt down some Dunham Technique classes when things are up and running again as nothing beats actually moving and feeling the style in your body. A shout out to all my fellow home-bound dancers out there: hold on in there, we’ll be back at it soon enough!

Thanks for reading